These days, the art marketplace writes art history, and what is best for the profit margin of the top buyers and sellers is not necessarily faithful to what is true, best for art, or conducive to understanding art, artists, reality, or each other. Au contraire, and in spades. The legend of Vincent’s extreme psychological distress—the myth of the “tortured genius”—is degrading to Van Gogh and a pox on living artists. In writing this article and making the video, I am well aware that people want Vincent to have sliced off the entirety of his ear in an incomprehensible state of psychotic rage and despair, just as they want him to have shot himself in the wheatfield. Saying otherwise is tantamount to claiming Christ was never crucified. Frankly, it’s bad for business.

Alas, I’m a stickler for the unvarnished truth, and I also know that exaggerating Vincent’s mental illness is an impediment to a genuine appreciation of his art. His paintings become props or illustrations for a sensationalist myth rather than the stories about his life being a backdrop to help us appreciate his art on its own terms for what it intrinsically has to offer. The artist’s work should and can easily stand on its own without us knowing anything at all about him.

You can watch the [shadow-banned] video version of this article here:

Before I launch into flipping the dominant ear narrative on its back, I want you to consider something Vincent said about himself:

Who is Vincent in the eyes of most people today? Is he still an unpleasant, eccentric nobody, or much worse, a violent madman who sliced off his own ear? Do we see his heart revealed in his paintings, or do we project insanity on top of them?

For all of my adult life, I’ve been annoyed by the way artists are depicted in film. I suppose it’s an attempt to make artists more interesting to the general public. Artists are portrayed as overly passionate and with no self-control, social skills, or sense of humor. It’s as if, in order to compensate for being creative, artists must be wildly deficient in most every other way. Movies about Vincent are among the most offensive, and Julian Schnabel’s “At Eternity’s’ Gate” is the worst of the bunch. On screen, Vincent is portrayed as a pathetic nutjob, perpetually straining at the end of his leash and slashing at his canvases in a psychotic fury. [The rare exception is “Loving Vincent”, which I’d actually recommend watching.]

Even documentaries reliably describe the painter as a “tortured genius” and a self-destructive martyr on a biblical scale. And here we come to my inspiration for writing this article. Several days ago, I watched a documentary about Van Gogh’s self-portrait with bandaged ear. The narrator was the award-winning, immensely popular English art critic, Waldemar Januszczak.

It was an informative and entertaining film, but something nagged at me. Why had Waldemar repeatedly stated that Vincent “cut off his ear” and never elaborated that it was only a portion of his ear? Why perpetuate a sensationalist myth rather than straightforwardly tell us the truth?

I went to look up a medical drawing I’d seen years ago showing the lower part of his ear was removed, but as relentless as I was in my search, I couldn’t locate it anywhere. Instead, all I could find was a new drawing that had been discovered in 2016 and told a different story.

On top of that, there were articles and videos everywhere asserting that, finally, based on this newly discovered drawing, we now finally know for sure how much of his own ear Vincent cut off.

The damning evidence turned out to be a sketch made by doctor Félix Rey, who had treated Vincent at the time. The drawing showed precisely where the ear had been cut. With the exception of a tiny, drooping section of the lobe, it had been completely severed.

The jury had come to a verdict. The case was closed. Vincent was a raving lunatic who sliced his ear clean off in a fit of psychotic fury.

It’s like I’d been in a coma for the last 7 or 8 years. How had I, an artist myself, missed this groundbreaking revelation about one of my very favorite all-time painters? This new verdict didn’t sync with my impression based on books I’d read as a young adult, including a compilation of Vincent’s letters to Theo. I was suspicious. But I had to be honest with myself. Was I just upset that I’d been wrong all along, and reluctant to accept that the most sensationalist accounts issuing from the tabloid newspapers of the time were actually correct? And we’re talking about the same level of journalism that reported Vincent as being Polish.

But right away, I found the evidence less than airtight. The drawing wasn’t made from direct observation, or for medical reasons, or when Vincent was hospitalized. It was sketched 40 years later for the novelist Irving Stone, who was penning the dramatic fictionalised artist biography, “Lust for Life.”

Dr. Rey wrote on the note, “happy to give the information you have requested concerning my unfortunate friend. I sincerely hope that you won’t fail to glorify the genius of this remarkable painter, as he deserves.”

The object here was to “glorify the genius” of Vincent in what was to become the most popular recounting of his life in literature and then in film. Would it be more glorifying and immortalizing for Vincent, and his doctor, if he were remembered as cutting his ear off? I was struck right away by this motive, which was, curiously, not to tell the plain truth.

A couple years prior, this same doctor had described Vincent in an interview as “a miserable, pitiful man, small of stature,” who always wore an overcoat, “smeared with colors,” since he “painted with his thumb.” In addition to being demeaning, we know that the description of his stature and painting technique is inaccurate. He was known to be medium-height and somewhat stocky, and he painted with brushes, as is clearly evident in a few of his self-portraits as well as by looking at the conspicuous brush strokes covering his canvases.

And so the final word on Vincent’s ear is traced to a man who had already inflated and distorted the truth about Vincent’s life.

The drawing is not the only argument, however, as there is further contemporaneous evidence. At the time of Vincent’s injury, according to the reportage in a local newspaper, Dr. Rey, Paul Gauguin, and a policeman said that Vincent had “cut off the ear.” However, this general phrase may have been used for shock value and doesn’t specifically address the extent of the injury.

It’s worth mentioning that most of what has been accepted as the definitive account of what transpired on the fateful night Vincent’s ear was cut comes directly from the intimate journals of Gauguin.

And Gauguin, as it happens, was the prime suspect when the police discovered Vincent lying nearly lifeless in his bloodied sheets. Scholars have advanced the theory that Gauguin, who went about with a saber and was an accomplished fencer, accidentally nicked Vincent’s ear while bluffing during their infamous altercation. Vincent, they argue, covered for Gauguin so that his fellow painter wouldn’t go to jail. The theory is impossible to prove, but it would be credulous to accept Gauguin’s version of the events wholesale, given his penchant for self-aggrandisement, as well as the possibility that his story could be an elaborate alibi.

I gather that it is much harder to believe a man who went about wearing a sword on his hip might brandish it and inflict a non-life-threatening wound on an adversary during a heated dispute than that the other man would go home following the altercation and slice his own ear clean off with a hand razor.

While art history has confidently declared Vincent cut off his entire ear after the confrontation with Gauguin, there’s better evidence that he only removed a portion. In addition to written descriptions, it also includes drawings by another of Vincent’s doctors and a little-known, unsettling self-portrait.

Three documented accounts assert Vincent’s ear was only partially severed.

1, A few months after the ear mutilation, pointillist painter Paul Signac paid Vincent a visit and claimed that it was, quote: “the lobe of the ear, not the ear.”

2. The son of Dr. Gachet, the doctor who cared for Vincent in his final weeks, including the time following his shooting and right up to his passing, saw the artist several times during that period. He has also stated that, quote: “it was not all the ear—as far as I remember—it was a good part of the outside of the ear (more than the lobe)” .

3. After his ear healed, Vincent went to see his brother Theo and his wife Jo three times in Paris, staying at their apartment for a total of six days. In her 1914 memoirs, Jo recalled that Vincent had, quote: “cut off a piece of his ear.”

Significantly, the accounts that he cut off all of his ear were in the immediate shocking aftermath of the event, mostly instantaneous impressions, and whatever remained of his ear would likely have been covered in blood, scabbing, and bandages. On the other hand, observations that only part of the ear had been removed were made long after it had healed and with hours, days, or weeks of opportunity to get in a good look.

But this is just the words of a few people versus a handful of others. The smoking gun was a drawing, which is a different caliber of evidence, so to speak.

What about the etchings and sketches that Dr. Gachet produced of Vincent on his deathbed? He drew the left side of Vincent’s head including the mutilated ear. The sketches were done immediately while Vincent lay in his casket, and the etchings were done shortly thereafter.

The sketch at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam shows a rough ear, and while the shape is not clearly delineated to my eye, it indicates something is there.

Since the artist was clean-shaven and his hair short-cropped, the shapes couldn’t be his beard or hair. This sketch is signed “VR,” which are the initials for “Van Ryssel,” which was Dr. Gachet’s artist’s pseudonym after the town where he was born. It is inscribed, “To my friend Theo Van Gogh, July 19th,” and also signed with “Dr. Gachet.”

While no writing by Theo addressing his brother’s ear exists, he was present at the funeral, and it defies logic that Dr. Gachet would send him a deathbed drawing with what looks like an ear if none were present.

A comparable sketch at the Louvre in Paris also indicates an ear but doesn’t go into enough detail for my satisfaction.

If there were only Dr. Gachet’s sketches, I would scarcely count them as conclusive evidence. It’s his etchings that are much more pertinent. Interestingly, Gatchet was the one who taught Vincent to etch, which is why Vincent was able to make a fantastic etching of Gachet.

It must have seemed only appropriate that Gachet reciprocate with an etching of his dead friend, his patient, and an artist whose work he collected and championed. I was able to track down four separate etchings Dr. Gachet illustrated based on his initial sketches of Vincent on his deathbed. One from from the Met in New York, another from the Art Institute of Chicago, a third from Emanuel Bayer of London, and the last from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. In each etching, the doctor clearly illustrated the mutilated ear.

The multiple variations reinforce one another so that it is unmistakably clear that the doctor was drawing the top of the ear, including parts of the helix, scapha, and the triangular fossa.

This is most clearly evident in the version at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Why are the sketches done by a doctor from direct observation at the time of Vincent’s death, as well as his further etchings, all dismissed in favor of a single rapid sketch made forty years later by another doctor?

If you’re still on the fence, hold tight because our main witness is about to take the stand. Enter what is probably Vincent’s most harrowing self portrait.

The “Self-Portrait” of 1889, or Oslo Self-Portrait, as it was named because it was housed in the National Museum of Norway in Oslo, was painted while Vincent was a patient at an institution for the mentally ill at Saint-Rémy in Provence. He painted it after his self-portraits with bandaged ear, and before his three final self-portraits.

This is the only painting he ever executed during a bout of psychosis, and in a letter to Theo dated September 20, 1889, he referred to it as “an attempt from when I was ill.” Notably, Edvard Munch, painter of “The Scream,” said “he found [this painting] scary, because of the gaze from the self-portrait staring back at him.”

Since the 1970s, the Oslo self-portrait was thought to be a fake. However, in 2020, after a five-year period of meticulous analysis, specialists from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam were able to confirm the painting’s authenticity.

The painting was made eight months after the ear slicing and it remarkably depicts precisely the same outer corner of remaining ear as shown in Dr. Gachet’s etchings.

While I am the only person I’m aware of who has compared these images, experts have ruled out the notion that the Oslo portrait depicts the severed ear.

According to Mark Brown, writing for the Guardian, for example

Van Gogh would have been looking in a mirror as he was painting so the ear in view is his right one, not the one he famously severed with a razor blade in December 1888. The ear in the Oslo painting is vague and presumably deliberately so.

Mark Brown, correspondent, The Guardian, Jan 21, 2020.

I looked carefully at the entire collection of the artist’s self-portraits, and this is the only instance where he did not clearly articulate the entirety of the ear. Nevertheless, the accepted argument maintains that it cannot be his left ear, because he must have painted the picture based on his mirror reflection, in which case we are seeing his right ear, and he merely chose to blend out the lower half of it for unexplained artistic reasons. End of story.

Unless you bother to look carefully at his very next self-portrait, simply titled “Self-Portrait 1889.”

At first glance you might think this corroborates the accepted version of reality. The artist has rendered himself at the same angle, and and in this image, his entire ear is visibly undamaged. However, there is an enormous problem. You might be able to work it out by yourself if you carefully examine the next two pictures:

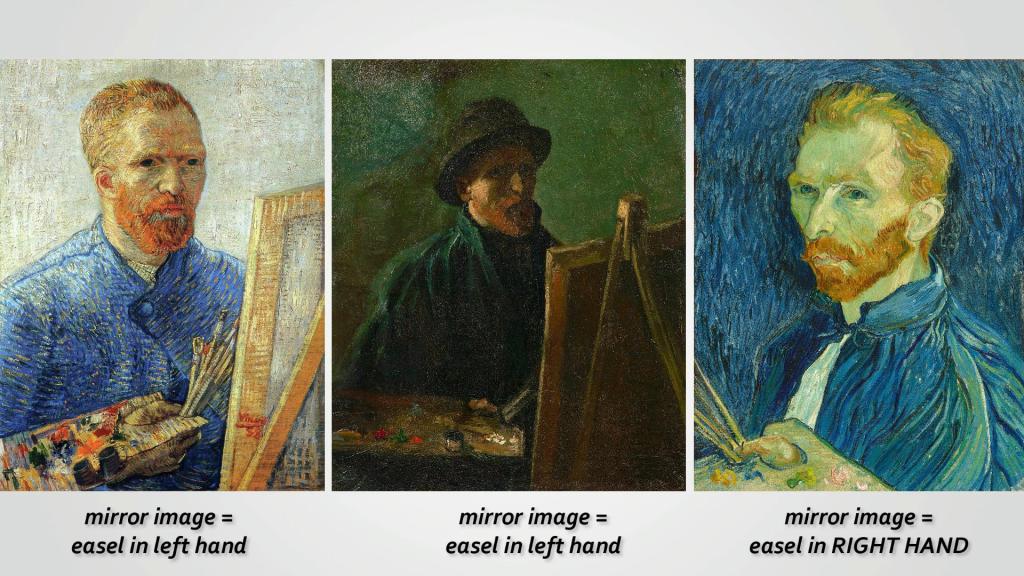

Both paintings show the artist holding his palette in hand. The other hand is doing the painting. In Self-Portrait in front of the Easel, January 1888, because it is a mirror image, he holds the palette in his left, non-painting hand. In Self-Portrait 1889, and which must also be a mirror image, he holds the palette in his right hand.

According to the Van Gogh museum: “Van Gogh was right-handed. We are almost certain of this, because in two self-portraits, he’s pictured with the pallet in his right hand. But because he painted himself using a mirror, you need to flip that image. Vincent is therefore actually holding the pallet with his left hand, and his brush in his right”

The second image they used was Self-Portrait as a Painter of 1887-1888.

We also know from portraits by Gauguin and John Russell that Vincent painted with his right hand.

The Van Gogh museum didn’t mention the third painting where Vincent holds his easel in his right hand, which would make him a left-handed painter.

The Self-Portrait of 1889 is impossible as a mirror image, and no one I know of has noticed or mentioned this. The painting can’t show his left side because his ear is intact, and it can’t show his right side because that would mean he’s holding his palette in his right hand. It can be confusing to try to flip images in one’s head, so suffice it to say that either way you look at it, the hand holding the palette can only be his left hand, in which case the corresponding ear can only be his left ear. But the ear is mysteriously intact. Somehow the left hand and left ear don’t match, in which case this painting is undeniably not a faithful copy of what Vincent saw in the mirror.

Whatever the explanation is for this conundrum, it proves that Vincent wasn’t restricted to painting mirror reflections. Furthermore, this portrait comes right after the Oslo portrait. How can we be so sure he relied strictly on a mirror image when painting the Oslo self-portrait, when he didn’t do so with the following self-portrait.

He could also have used any number of techniques, including relying on just his imagination. He painted The Red Vineyard and The Starry Night from observation, memory and imagination and, somewhat more to the point, he painted himself on the way to work in Self-Portrait on the Road to Tarascon, 1888.

It does not follow at all that the Oslo Self-Portrait must have been created faithfully using a mirror, given that the self-portrait that comes immediately after it cannot be a mirror image painting, and because Vincent has demonstrated that he is capable of painting from the imagination, including portraying himself.

There is only one reason given that the painting doesn’t depict Vincent’s mutilated ear, despite it looking exactly like that, and that is the argument – which I just proved false – that he never deviates from mirror images.

All of the more thorough evidence points to a section of Vincent’s ear being sacrificed, not the entirety. Nevertheless it’s been decided that the words printed in the tabloid clickbait of the day, the apocryphal boasting of Gauguin, and the suspect doodle of a doctor known to widely bend the truth about Vincent are incontestable facts.

Why Does It Matter?

Why did virtually every newspaper, news program, art institution and expert who covered the discovery of Dr. Rey’s drawing so easily conclude that Vincent cut off his entire ear, and disregard the prior belief that it was only part? Why didn’t they take Dr. Gachet’s etchings into account? My hunch is that it’s the same mentality that is behind the laughably pathetic romanticized portrayals of artists we see in feature films, and the more outlandish the caricatures the better.

In the case of artists and Vincent in particular, how we perceive the artist and how we appreciate the art are intertwined. While it likely sells more tickets to display the paintings of an alleged raving lunatic and “tortured genius” who cut off his own ear, it dehumanizes the artist, makes him “other”, nearly impossible to relate to, and views him through the lens of sophomoric sensationalism and malicious gossip. We continue to portray him as his neighbors who signed a petition to have him ousted from the community saw him, or else how he was perceived by the boys who mocked him and pelted him with rocks. We make of the man a circus show freak, and at worse appreciate his art in the way people value and purchase the clown paintings of serial killer John Wayne Gacy: not for their inherent merit, but as conversation pieces.

Vincent was a great artist in spite of, not because of his bouts of mental illness. The startling clarity of paintings that were made in a state of calm, that are about humility, vibrant nature, exulting in color, capturing the essence of life, and conjuring love, can end up clouded with an acidic varnish of our own projected demeaning cliches.

We deny his humanity when we exaggerate his insanity.

Consider what Gauguin wrote about Vincent after moving in with him in the Yellow House in Arles, and before the ear slicing incident:

““I don’t admire the painting but I admire the man… He so confident, so calm. I so uncertain, so uneasy…” Vincent, confident? Calm? Gauguin wrote about the house, “In spite of all this disorder, this mess, something shone out of his canvases and out of his talk, too…. He possessed the greatest tenderness, or rather the altruism of the Gospel.”

Do we look at Vincent’s paintings as if they were painted by someone “calm, confident, possessing the greatest tenderness, and the altruism of the Gospel”? THAT would be vastly superior to seeing them as a record of the fevered lashings of a self-mutilating maniac.

And instead of seeing the man as a “tortured genius”, consider how he saw himself, which is evident in the following quote

A painter really ought to work as hard as, say, a shoemaker… I plow my canvases as [the peasants] do their fields.

And this following quote is from the last letter that he wrote to his mother and his sister, describing one of his canvases.

I myself am quite absorbed in that immense plain with wheat fields up as far as the hills, boundless as the ocean, delicate yellow, delicate soft green, the delicate purple of a tilted and weeded piece of ground, with the regular speckle of the green of flowering potato plants, everything under a sky of delicate tones of blue, white, pink, and violet. I am in a mood of almost too much calm, just the mood needed for painting this.

While truly understanding Vincent requires grappling with his mental condition, and includes taking into account his paintings with bandaged or even an exposed mutilated ear, it’s time for us to let the man out of the straightjacket of grotesque exaggerations of his mental illness. In this way we also cleanse our own eyes before his paintings, we allow his spirit and his illuminated canvases to radiate warmth and clarity, even if it’s not good for the bottom dollar.

I am not saying I know for sure how much of Vincent’s ear was shorn off, by whom, or whether Vincent painted his disfigured ear in the Oslo self-portrait or not. Here I gave the reasons I am not convinced by the scant and eyebrow-raising evidence that absolutely persuaded others that he cut off the entirety of his ear. What I am certain of is that the proclivity to portray Vincent as an extreme caricature hinders our understanding of his work and does him a major injustice. It further highlights a propensity to stigmatize people who are experiencing mental health problems, and is an impediment to understanding how art addresses the human condition, and to appreciating art in general.

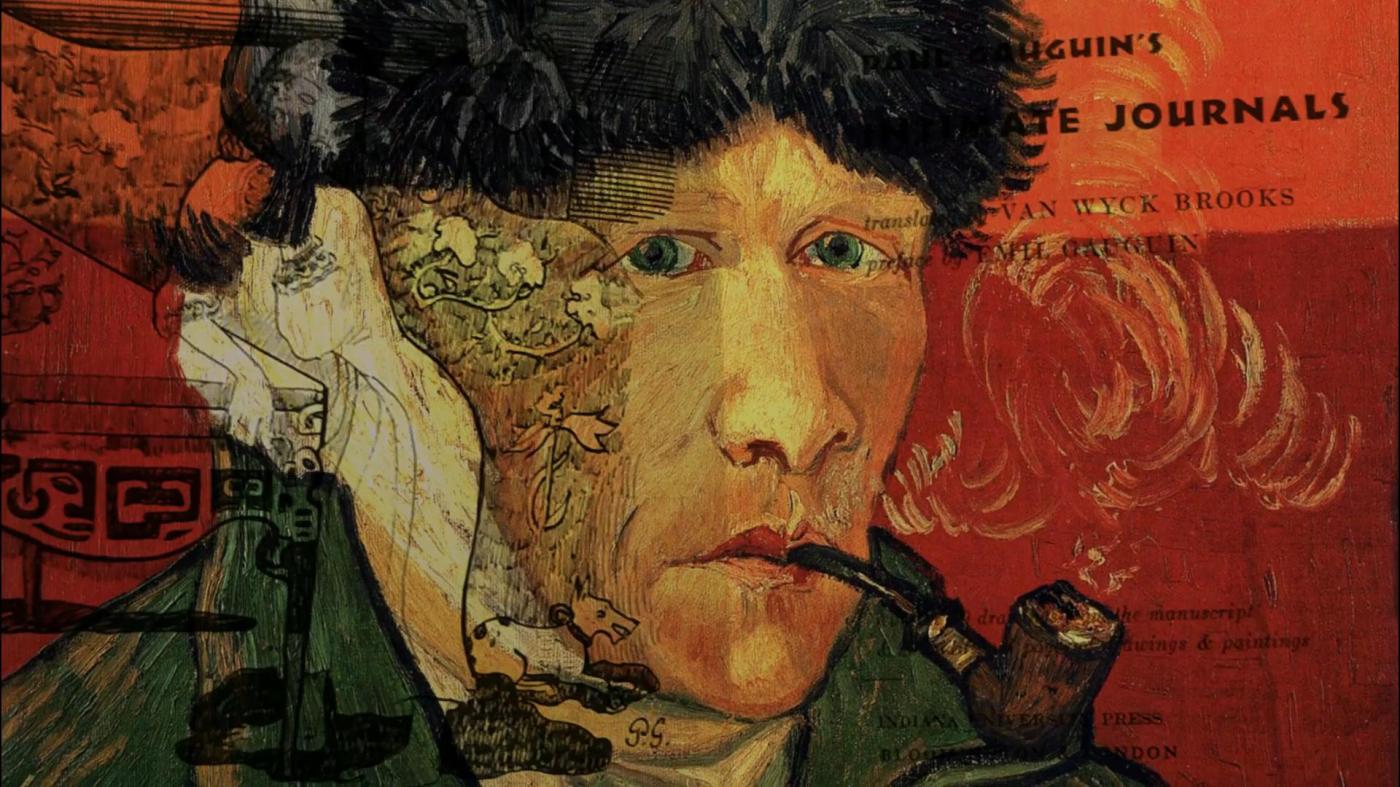

And now, as promised, here is my own homage to Vincent in the form of a digital impasto painting using my own custom techniques, and portraying him as if he did a self-portrait with a freshly cut ear.

And this is where my vested interest I confessed to comes into play. I completed this artwork in 2016, and was not aware of Dr. Rey’s drawing. And so, in retrospect if everyone is right I got the ear all wrong. It’s art, so that isn’t such a big deal, but it turns out I may have been closer to the truth all along. This image has been sold on the internet by other people for years and for up to hundreds of dollars a pop, but not only did I not get a cent for any of it, they are inferior copies because they were taken from small Jpegs lifted from my website.

Now, finally, I’m making available hi resolution archival prints, posters, cards and other products based on my full scale image that only I can provide: Imagined Van Gogh Self-Portrait with Cut Ear.

Hope to see you again for another adventure in art.

And if you like my art or criticism, please consider chipping in so I can keep working until I drop. Through Patreon, you can give $1 (or more) per month to help keep me going (y’know, so I don’t have to put art on the back-burner while I slog away at a full-time job). See how it works here.

Or go directly to my account.

Or you can make a one time donation to help me keep on making art and blogging (and restore my faith in humanity simultaneously).

👂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for an interesting read.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I admire your researches!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed. In French “il s’est coupé l’oreille” doesn’t mean “he cut his ear (off)”. Just he cut himself. You could say “is s’est coupé un doigt”, “he cut a finger”. Doesn’t mean – at all – that he cut his finger off.

And furthermore agreed about the “artistic” rendition of the “doomed artist”. He probably had issues, but what matters is his work.

You quote a letter of his many letters to Theo. I imagine those letters have been published haven’t they? That should eliminate most drama.

Thanks for the post.

Cheers

LikeLiked by 1 person